The American Music Club Gets Happy (Sort Of)

by Tony Sclafani

The American Music Club has never had the reputation as a shiny, happy band. The melancholic leanings of songwriter Mark Eitzel have more in common with the gritty, booze-fueled writings of realist poet/author Charles Bukowski than pop tunesmiths. Since the band’s inception in the early 1980s, Eitzel has infused the group’s music with the type of broken-hearted poetics that gets the attention of writers but not the public (except when the poet in question happens to die young, which Eitzel didn’t). His dark, moody vocals and the sustained drones of longtime lead guitarist Vudi (Mark Pankler) combine to spin a dreamlike soundscape that’s more or less stayed intact through the group’s nine albums. It’s kind of like The Blue Nile with more blues – and more nihilism.

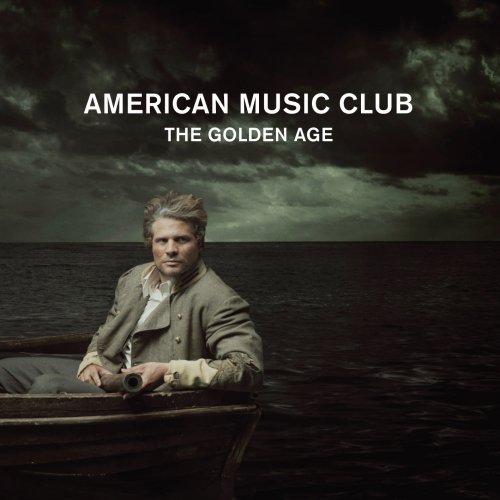

All of the above is probably the reason the group has generally flown under the radar in the country after which it’s named. The band’s formula has evolved a bit, though, on The American Music Club’s newest release, The Golden Age, a largely acoustic effort. Although by no means a happy-go-lucky CD, The Golden Age shows a new, warm side to Eitzel’s writing, and even flashes of humor. There are deliberately impish lyrics (like the line “all I can give you is one of my stupid songs” from “Who You Are”) and tongue-in-cheek arrangements (such as the German oompah-band feel of “I Know That’s Not Really You”). Eitzel says it’s all part of a new mindset he’s found since refounding the band in 2004.

“For me the whole struggle I’ve had in the last few years is people thinking I’m like this master of dark, dark music and the sun never rises on my world,” he says by telephone from his car. “And that’s simply not true. That’s one thing that always drives me crazy. I am a dark person and I like serious stuff, but that ain’t totally me.”

The record is the band’s ninth, but only its second since Eitzel and guitarist Vudi reconvened with new bassist Sean Hoffman and drummer Steve Didelot. This time around, Eitzel’s anger seems largely supplanted by hopeful romanticism. He’s arguably never sounded more beguiling than on unapologetic love songs like “All My Love” and “The Stars.” The group’s music has also arguably never sounded more commercially viable than on its sweetly melodic single “All the Lost Souls Welcome You to San Francisco.”

Before its 2004 reunion, The American Music Club was last heard from in 1994, when they released the CD San Francisco, a fine effort which failed to sell as expected. The group had always had limited cult status, but lack of money became a crucial issue in the mid-1990s, Eitzel says. Once he saw the band “didn’t have any unity,” he embarked on a ten-year solo career (which included West, a 1997 album recorded with R.E.M. guitarist Peter Buck).

“San Francisco was supposed to be a big commercial album for us,” he says. “I wanted to keep the band together so I tried to write all these commercial songs. But in the meantime the band had run out of money. And half the band wouldn’t tour without the money.”

Three years before, the group had enjoyed its greatest success with the critically-acclaimed Everclear. While that album wasn’t a huge hit, it pulled the band out of near-total obscurity, where it had been languishing since it got its start playing San Francisco new wave clubs alongside groups like Translator (“Everywhere That I’m Not”) and Romeo Void (“Never Say Never”).

“They were kind of successful compared to me,” Eitzel says of those groups, both of whom signed with the 415 Records/Columbia Records powerhouse, while The American Music Club jumped from one indie label to the next. “The woman from Romeo Void (Debra Iyall) came to one of my shows and said ‘Nah, this sucks!’” he laughs.

Part of the band’s problem was that it got off to a shaky start, since its first release was a quickie album created “because we were going to Germany and we needed something to sell,” Eitzel says. Although the All Music Guide says the band “disowned” the release, Eitzel says that’s not true, and he thinks “there’s good stuff on it,” even though “it’s very obvious what my influences were at the time. I really loved Joy Division.”

The other blockade to a larger audience was that the band refused to be confined to a genre. Listening to them can feel like standing in Four Corners, U.S.A., where four states meet and you can see Arizona, New Mexico, Utah or Colorado depending where you look. Similarly, depending on your vantage point, you can hear The American Music Club as folk/rock, alternative rock, poetic pop, or even easy listening. And the label “Americana” doesn’t cut it, because that implies old-timey fiddles and the like, which The American Music Club never regularly used. All of this isn’t lost on Eitzel, who admits to being influenced by music ranging from British folkie John Martyn to The Beatles to glam rock, punk rock, and prog. “I loved it all, you know?” he says.

The group reconvened almost by accident. Vudi had put together a band in Los Angeles and Eitzel liked what he heard. At the same time, reunion talks with the band’s previous drummer and bassist, Tim Mooney and Danny Pearson, stalled. “I kept saying let’s go to L.A. and work with Vudi, and every time I’d see them or talk to them it was just negative,” Eitzel recalls. By contrast, he says, he found newbies Hoffman and Didelot “so positive and so bright.”

Vudi’s new band became the new American Music Club that recorded the 2004 release Love Song for Patriots. That album received rave reviews from a variety of publications, notably Paste magazine. It also didn’t hurt that artists like My Morning Jacket and Jack Johnson had made vogue the kind of thoughtful guitar pop that the band had been doing all along.

Eitzel’s attitude may have changed, but his approach to writing lyrics hasn’t. His story-songs still come across so personal that they seem like diary entries. This has been a facet of both The American Music Club’s work and Eitzel’s solo albums and the singer-guitarist says it’s unlikely to change.

“I can’t write a song without referencing something in the real world,” Eitzel admits. “It’s gotta be things I hear, or somebody I’m talking to, or somebody I see that corresponds with something I’m thinking about in my own life. In that way it becomes personal. Like (the albums) California and Mercury and Engine — all those things were about my parents passing away. And also, they were about me just not wanting to come out of the closet, which was kind of torturous for (gay people of) my generation. I don’t think it’s torturous for people ten years younger than me. I always make it about my life and if it’s too much about my life, then I hide it with lots and lots of bad metaphors and rhyme.”

Golden Age listeners will be privy to a blow-by-blow account–“The Windows on the World”–of a night on the town in New York Eitzel and a friend had in a World Trade Center bar. “The song is kind of everything that happened,” Eitzel confesses. “As we were walking into the place I was like ‘This is great! Is there gonna be a band? God I hope not.’ So I went to the woman behind the bar and I said ‘You know, it’s so beautiful up here, you can see forever.’ And she said ‘Do you want a drink or what?’” Eitzel milks both humor and heartbreak out of such New York attitudes in his song.

On “All the Lost Souls Welcome You to San Francisco,” Eitzel says he wanted to write a number that could rival “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” as a love letter to his longtime adopted hometown (Eitzel grew up in a nomadic military family). “That song is one of the perfect songs,” he says of the standard popularized by Tony Bennett. “I really love it. So I thought I would write my own tribute.”

One of the odder aspects of The American Music Club’s history is the fact that the band has always been more popular abroad. The lack of a commercially identifiable sound might have kept the band from success at home, but that hasn’t proven a debit in Europe, where Eitzel and the band will travel a few days after our interview.

“Europeans actually get American music in a way that Americans don’t,” Eitzel says. “Isn’t it weird that I can draw more people in Italy or France than I can in Illinois? They appreciate America more than Americans do.”

Leave a Reply